“Kuwalipikado” and Other Cases of “Salitang Siyokoy”

Filipino is a lovely language—quirks and all.

Two days ago, I posted about the word kuwalipikado and how it is not actually a real Filipino word:

For some reason, it still blows my mind that "kuwalipikado" is not a real, recognized, grammatically correct #Filipino word, and the actual recognized word is something that I've never met or heard of my entire life up until I learned about its existence—"kalipikado".

That post turned into a thread about a class of Filipino words called salitang siyokoy (literally merman words in English).1 To understand what salitang siyokoy are, we have to understand that the Philippine national language Filipino was standardized with the express intent of being flexible so it can incorporate vocabulary from other languages—English, Spanish, and local and native languages in particular. In Filipino, there are three main ways of how loan words are borrowed into the language:

-

Using the word as-is. When you borrow words from

other languages, you can use the word with no modifications to its

spelling outside of conjugations. For example, the English

sentence

I liked your post on Mastodon

can be translated into Filipino asNa-like ko na ang post mo sa Mastodon,

using the English like as is and putting a na- prefix to denote past tense. - Respelling the word in Filipino while trying to preserve the original sounds as much as possible. This is probably the least favored way of borrowing loan words because respelling foreign words in Filipino can make the words look funny, or even worse, too foreign to understand. This method works for words like iskédyul (schedule), trápik (traffic), and pulís (police). But it starts to break for other words like Kok (Coke), bukéy (bouquet), and in the case of baguette, the Filipino respelling bagets already has a different meaning.

- Translate first to Spanish, then respell in Filipino. The Philippines was under Spanish colonial rule for 333 years, and so even if the population largely stopped speaking Spanish and turned to English, it is still favorable to the Filipino ears to hear loan words that sound like Spanish. So for words that would look funny should they go through the second method, this third one works best. For example, baggage is better translated to Filipino as bagahe (from Spanish bagaje) rather than a direct respelling into bageyds. Island is also better translated to Filipino as isla (from Spanish isla) rather than a direct respelling into ayland.

The English words qualified and

qualification can actually go through these three

methods, and they’re all going to be valid Filipino words. Take the

sentence

You weren’t accepted for the job because you are not yet

qualified. Reach the qualifications first before you

return here.

All three of these Filipino sentences would be valid:

-

Hindi ka natanggap sa trabaho dahil hindi ka pa qualified. Abutín mo muna ang qualifications bago ka bumalik dito.

-

Hindi ka natanggap sa trabaho dahil hindi ka pa kwalifayd. Abutín mo muna ang mga kwalifikeysiyon bago ka bumalik dito.

-

Hindi ka natanggap sa trabaho dahil hindi ka pa kalipikado. Abutín mo muna ang mga kalipikasyon bago ka bumalik dito.

Whichever one of these is used is totally up to the writer. Although each of these sentences mean the exact same thing, each of them carry a different vibe. The first sentence carries a more informal day-to-day feel; it’s a sentence you can actually hear a common person say. The third one carries a more formal, more dignified sound. I imagine very few would actually prefer the second sentence featuring the direct respelling from English because, for one, the words look funny, and second, although the sounds would be familiar to speakers, it doesnt look familiar so I think people would get confused with those translations.

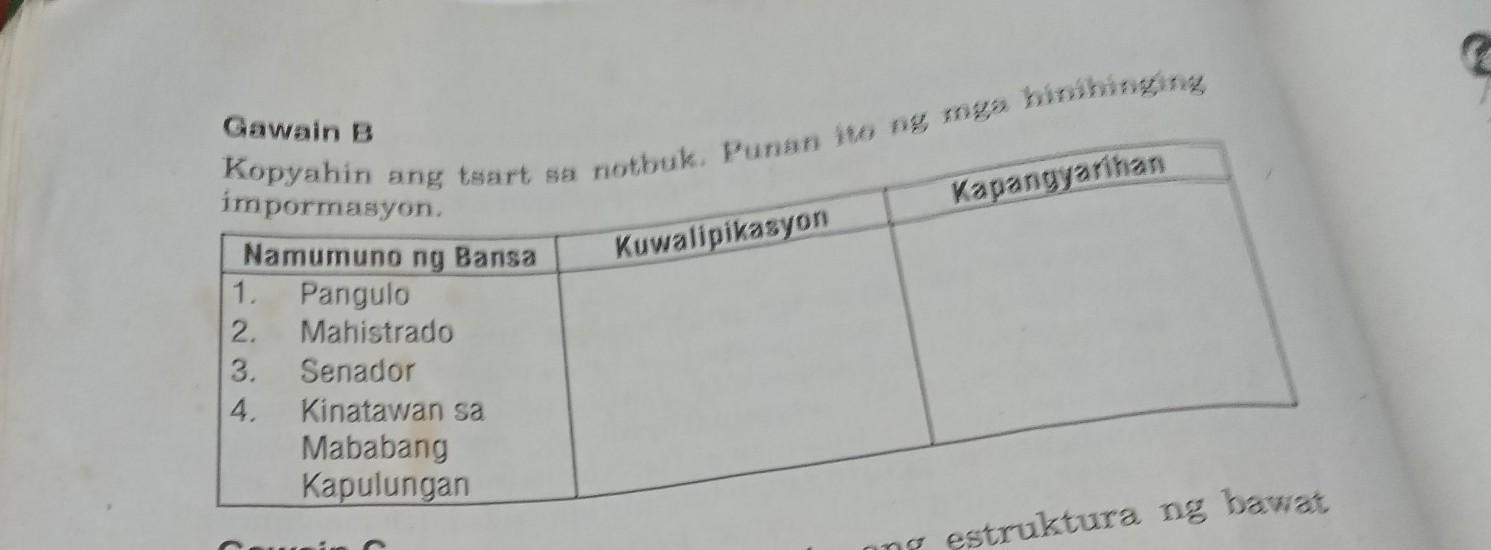

But I want you to focus on the translations of qualified and qualification in the third sentence. We use kalipikado and kalipikasyon. Now look at these examples from Filipino media:

So what’s happening here? In all the three forms of the Filipino words for qualification, we have never once encountered kuwalipikasyon, or even kwalipikasyon. Where did this form come from? That is where salitang siyokoy comes in. The book Manwal sa Masinop na Pagsulat2 defines salitang siyokoy as such:

Mag-ingat lang sa tinatawag na salitang siyókoy ni Virgilio S. Almario, mga salitang hindi Espanyol at hindi rin Ingles ang anyo at malimit na bunga ng kamangmangan sa wastong anyong Espanyol ng mga edukadong nagnanais magtunog Espanyol ang pananalita.

(Beware of what Virgilio S. Almario calls merman words, words that do not look quite like Spanish nor do they look quite like English and are often due to lack of knowledge in proper Spanish forms by the educated who want to sound Spanish in speech.)

This is exactly what kuwalipikasyon and kuwalipikado are. In an attempt to make it sound Spanish, someone somewhere took the English words qualified and qualification, mashed the Spanish suffixes -ado and -ación to its butt, then respelled it in Filipino. But qualificado and qualificacion are not real words in English or Spanish. The actual words are calificado and calificacion. But the term has spread and all of us (me included) are none the wiser. It took me years before I found out that the word I kept using everywhere didn’t really exist! It took me staring at my screen on KWF Diksiyonaryo for like an hour to actually start accepting this new (to me) discovery.

But of course, languages are alive and dynamic. There’s a case to be made for words that just pop out of thin air. After all, a lot of Filipino words come from gay slang3 and have assimilated into the language that people, mostly homophobic ones, often get surprised when the etymology of the words reveal their origin.

And there are cases of salitang siyókoy where the invalid word has taken a divergent connotation from the actual word, like the Filipino word for image, imahen (from Spanish imagen), which is now almost exclusively used in religious contexts while the salitang siyókoy imahe (probably from a mistaken assumption that the word imaje exists in Spanish) is used as the direct translation of the word for every other non-religious contexts.

Regardless, what are grammatical rules if they are not meant to be grammatically broken? I just found it fascinating, so much that I wanted to look more into it and write. As for me, I will stop using the siyokoy term from now on, but if you want to keep using it, who am I to judge? Languages are very fascinating and they are alive.